Army Scientists Develop Cutting-Edge, Durable 3D Printing Technology

THE DUAL-POLYMER TECHNOLOGY

“Conventional polymer filaments for 3D printing are made up of a single polymer,” Wetzel said. “Our innovation is that we’ve combined two different polymers into a single filament, providing a unique combination of characteristics useful for printing and building strength.”

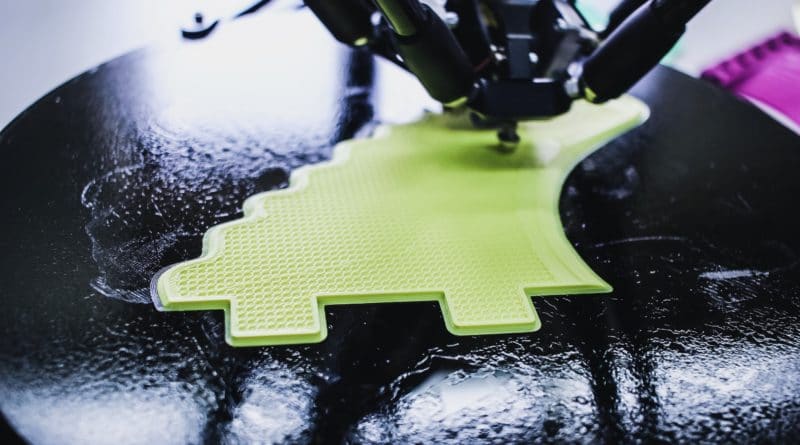

The dual-polymer filament combines acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, or ABS, with polycarbonate, or PC. A critical design feature of the filament is that the ABS and PC phases are not simply mixed together, a common approach for creating blended polymers. Instead, a special die-less thermal drawing process developed by ARL is used to create an ABS filament with a star-shaped PC core. Once coupled, the filament is used as feedstock in a desktop fused-filament fabrication, or FFF, printer to create 3D prints with a heavy-duty ABS/PC meso‐structure.

FFF printers work with a heated nozzle that emits thin layers of melted plastic, similar to molten glass. The filament is deposited onto a print bed, one layer on top of another until it forms the 3D printed part. In order to fabricate a unique part, the nozzle, print bed, or both move while the hot plastic streams down.

The two polymers found in the new filament technology have distinct melting temperatures, Wetzel said.

After the solid bodies are initially printed, they are put in an oven to build strength. During this annealing process, the deposited material layers fuse together while maintaining their geometry and form. This stability is caused by the higher temperature resistance of the built-in framework.

“The second polymer holds the shape like a skeleton while the rest of it is melting and bonding together,” Wetzel said. “Through a series of filament design trials, we were able to identify that the star-shaped PC core provided a superior combination of part toughness and stability compared to other arrangements of ABS and PC in the filament.”

Current filaments — traditionally consisting of a single thermoplastic — produce parts that are brittle and weak, and would deform excessively during the annealing process, he said.

“We focused in on what can we do to improve those mechanical properties,” he added. “We wrote a series of papers getting very fundamentally down to the details of exactly why conventional single-polymer parts are not sufficient, what’s happening in the physics of the polymer — really at a molecular level — that prevents conventional printed polymer parts from meeting these requirements.”

The legacy thermoplastic deposits like a hot glue gun, he said. As the layers build, they don’t stick very well to the previous layer because by the time the second layer adds, the first one is cooled off.

“So, you’re not melting the layers together, you’re just solidifying material on top of one another, and they never really bond between layers,” Wetzel said. “Our technology is an approach that allows us to use these conventional desktop printers, but then apply post-processing to dramatically improve the toughness and strength between layers.”

“Manufacturing at the point-of-need provides some exciting possibilities,” Wetzel said. “In the future we can imagine Soldiers deployed overseas collaborating with engineers in the United States, allowing new hardware concepts to be designed and then sent as digital files to be coverted into physical prototypes that the Soldiers can use the same day. This paradigm shift could allow us to innovate at a much higher speed, and be keenly responsive to the ever-changing battlefield.”